Africa Before Europe Had Maps: What History Actually Shows

Africa Before Europe Had Maps: What History Actually Shows

Before European cartography, Africa was already known, connected, and navigated through trade routes and knowledge systems. Here’s what history actually shows.

Africa Was Never a Blank Space. One of the most persistent ideas about African history is subtle but powerful: that Africa was somehow unknown until Europe began drawing it. The phrase “Africa before Europe had maps” is often used casually, sometimes defensively, sometimes rhetorically. But behind it lies a serious historical question: Was Africa geographically understood before European cartography? The evidence says yes, clearly, consistently, and without controversy among serious historians. What did not exist in large numbers were surviving African paper maps in the European sense. What did exist were deep systems of geographic knowledge, transmitted through trade, travel, memory, and scholarship. The mistake comes when modern readers confuse difference with absence.

Mapping Is Not Just Paper and Ink

Maps, as we know them today, are a relatively recent cultural technology. For most of human history, people navigated space using:

• remembered routes

• named landmarks

• stars and seasons

• oral instructions

• lived familiarity with terrain

This was not unique to Africa. Medieval Europe itself relied heavily on itineraries and verbal geographic descriptions. Many European maps before the modern era were symbolic, religious, or schematic rather than accurate by modern standards. So when asking whether Africa had maps, historians first clarify: What kind of maps, and for what purpose?

Africa Was Geographically Known Long Before Colonization

By the early medieval period, Africa was already integrated into Afro-Eurasian networks of movement and knowledge. From at least the 8th century CE, trans-Saharan trade routes connected:

• West Africa

• North Africa

• the Mediterranean world

• the broader Islamic intellectual sphere

These routes were not improvised paths through an unknown continent. They were:

• well-established

• seasonally timed

• supported by known oases

• anchored by cities

Places such as Gao, Walata, Djenné, and Timbuktu functioned as geographic constants, reference points that traders, scholars, and travellers could reliably locate and describe. That is geography in practice.

How Knowledge of Africa Travelled

Much of what we know about early geographic representations of Africa comes from Arabic and Islamic scholars, whose works survive in greater numbers than local African records written on perishable materials. By the 9th–12th centuries:

• African regions were named

• major rivers were identified

• cities were located relative to one another

• climates and distances were described

Scholars such as al-Idrisi compiled geographic works based on merchant reports, traveller accounts, and administrative knowledge. Importantly, this information did not originate in a vacuum. It depended heavily on African informants, traders, and residents. Africa was being described because Africa was already being explored.

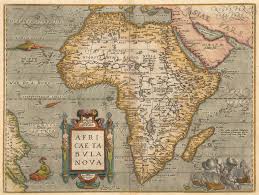

Early European Maps Did Not Start From Nothing

When European cartography expanded in the 15th century, it did not suddenly “discover” Africa. Early European maps:

• borrowed heavily from Arabic geographic traditions

• reproduced African place names already in circulation

• reflected existing trade knowledge

Surviving maps from the late 1400s show:

• African coastlines

• inland trade cities

• river systems

These details were possible only because Africa was already known, not because Europeans had just arrived, but because centuries of interaction had already taken place.

Did Africans Make Their Own Maps?

This question deserves honesty. What the evidence supports:

• There is no large surviving archive of pre-European African paper maps comparable to European collections.

• This absence is acknowledged by mainstream scholarship.

What the evidence also supports:

• African societies preserved spatial knowledge through oral, social, and practical systems.

• Trade, migration, and governance relied on accurate geographic understanding.

Historians caution against assuming that all societies encoded space visually on parchment. Many did not and did not need to.

To claim vast destroyed map archives without evidence would be speculation. CYSTADS does not do speculation.

Why the “Africa Was Unmapped” Myth Took Hold

Colonial narratives narrowed the definition of knowledge to what Europe produced and preserved. By defining “map” as European, written and archived in European institutions. Colonial discourse could describe Africa as empty, undefined, waiting to be organised. Modern historical research rejects this framing. Africa was known, named, navigated, and inhabited long before colonial borders were drawn.

What History Actually Shows

Based on credible scholarship:

• Africa was geographically understood long before European colonisation

• African regions were integrated into global knowledge networks

• European maps were cumulative, not original discoveries

• The absence of African paper maps does not indicate ignorance

Africa was never a blank state, it was a lived one.

Why This Still Matters

Understanding this corrects more than a historical error. It challenges the idea that:

• legitimacy comes only through European documentation

• knowledge begins when Europe records it

CYSTADS exists to restore memory without exaggeration, without apology, and without myth-making.